1918. The war is over and Germany sets about licking its wounds. Production of aero engines is promptly prohibited, robbing the recently established Bayerische Motoren Werke AG of its only product line. New ideas are required. The logical place to start is with engines, given the ready supply of production facilities and skilled workers. The question is: what kind of engines and for what purpose?

Tricky endings.

The First World War fast-tracked a host of new technologies from theory into practice. It also pitted resourceful engineers against one another like never before to see who could come up with the best ideas. Without the war, the progress of aircraft development would without doubt have been far slower, not least because the resources ploughed into it would have been meagre in comparison. Indeed, the cessation of hostilities saw the taps of investment swiftly turned off, bringing the whole operation more or less to a standstill. With its by then widely renowned aero engine firmly on the banned list, BMW AG found itself in urgent need of a new product.

Easy beginnings.

BMW knew a bit about building engines, that much was clear. But a large engine it created for boats and trucks was only moderately successful. Happily, the company’s fortunes took a turn for the better with the conception of a small unit for motorcycles. The finishing touches were put to the 500cc, 6.5-horsepower engine in 1920. It was christened a “boxer” design on account of a cylinder arrangement that featured horizontally opposed pistons moving in opposite directions (like a boxer’s fists). Customers were quick to cotton on to its appeal. Nuremberg-based company Victoria used it to power its motorcycles – to great effect. And fellow manufacturer Bayerische Flugzeugwerke also changed tack, but it only built the motorcycles around the engines, not the engines themselves. Unfortunately, the construction of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke’s Helios model revealed various flaws and when the BMW brand was transferred to the company’s ownership in 1922 there were fears it could suffer considerable reputational damage. Consequently, there was a keenness within BMW to come up with a whole new design as soon as possible.

Taking it to the Max.

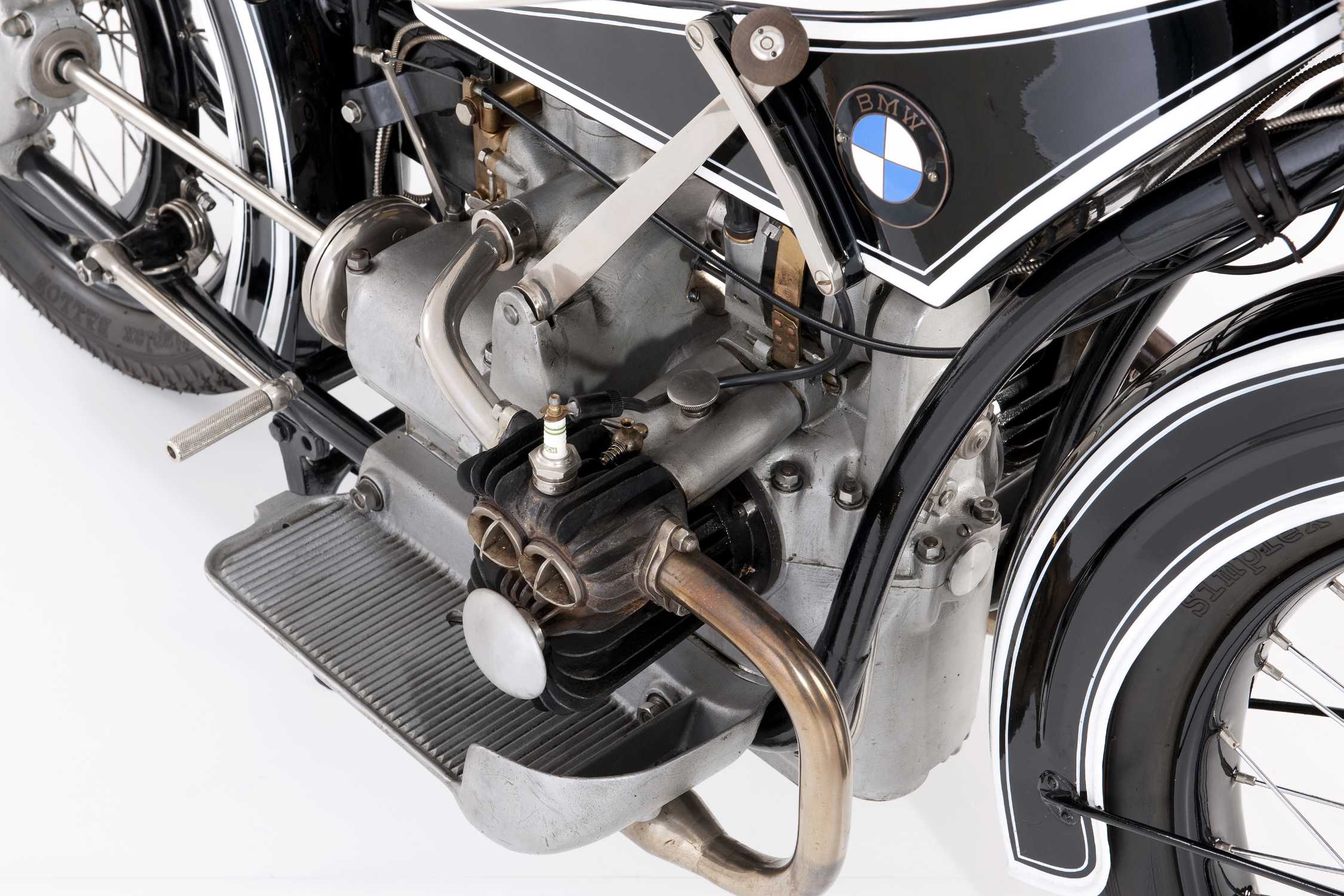

Having provided impressive evidence of his engineering skill with the IIIa aero engine, Max Friz was now exploring pastures new. Next up was a motorcycle, but for that he needed some peace and quiet. His solution was to move a large drawing board into the guest room of his house opposite the plant site. So it was that, in December 1922, these hushed surroundings witnessed the birth of a new motorcycle. Its signature feature was a “boxer” engine, whereby its cylinders lay horizontally to the direction of travel. For generations of riders ever since, BMW motorcycles and boxer engines have been inextricably linked. Friz favoured a robust cardan-shaft drive over a chain or belt, and bolted the gearbox directly to the engine. The result was a refreshingly harmonious motorcycle, one which was immediately well received. It was unveiled to the public as “The touring bike from Bayerische Motoren Werke” but known in-house as the R 32. The R 37 unveiled a year later was marketed as the “Sportmodell”. The model naming system familiar today wasn’t introduced until the arrival of the R 42.

A strong showing from the new kid on the block.

BMW presented its new motorcycle model at the Berlin Exhibition in autumn 1923. With 132 other manufacturers also attending, competition was fierce and it would have been easy to sink without trace. Handily, BMW had something special to show, courtesy of Max Friz’s enduring engineering brilliance. This may have been the first time in his life that Friz had turned his mind to a motorcycle, but the results left the assembled experts open-mouthed; before them was no longer a motorised bicycle, but a whole new vehicle.

The R 32 stood out from the pack through the unaccustomed smoothness of its surfaces, and the structure of its frame – with two fully-enclosed steel pipe loops – was new. The engine was positioned low, which ensured excellent roadholding, and the inky black paintwork and white trim lies created a suitably smart look. In the wake of the currency devaluation in Germany, the BMW motorcycle retailed at 2,200 marks, making it one of the most expensive models on the market. Not that this stopped it selling in large numbers.

Central to the bike’s success – alongside its trend-setting conception – was its reliability and material quality. Here was a show of strength from a company whose customers in its days as an aero engine manufacturer could not just pull over at the next cloud to fix a spluttering engine. BMW also passed every test with flying colours when it came to expertise with new lightweight alloys – deployed here in the engine’s pistons and soon in benchmark-setting fashion with the smallest details.

Success follows success.

Soon the company was pulling off eye-catching feats in motor sport events as well, which acted as a very effective advertising tool to boost sales. Ahead of the official model unveiling in Berlin, Max Friz had already put his creation – honed into a race machine by engineer Rudolf Schleicher – under the spotlight in the “Fahrt durch Bayerns Berge” comparison race through the Bavarian mountains. The scene was set for BMW to notch up its maiden race victories in 1924 and finish the year with its first German championship title.

This was to be only the start of an unprecedented run of success, one which was kick-started by the R 32 and which set BMW on a path to becoming one of the great vehicle manufacturers.