Wars have always been a motor for progress. In the struggle against their foes, nations would enter a frantic race to gain superior technology and firepower. As a result, resourceful design engineers have helped to decide the destiny of wars. In 1917, the BMW IIIa aero engine sent out a strong signal. Its output was greater than that of its opponents, while its operating reliability was also impressive. It thereby provided the underpinnings for the success of a company that was just starting out – with the express purpose of building that particular engine – but would go on to become a global player: BMW.

The modern war.

In the early days of the First World War, aircraft did not play a major role. With aviation still in its pioneering days, they were little more than flying crates, whose daredevil pilots were more likely to perform circus acts than provide any form of military benefit. But that was set to change, because the enemy, its troop movements and formations could be best observed from the air – an invaluable advantage for strategists needing to pass on orders to their troops. It wasn’t long before the skies were filled with new types of aeroplanes, whose crews had special cameras trained on the ground. Aerial dogfights soon broke out and heroes were made, their names going down in history. Manfred von Richthofen, aka the Red Baron, was a prime example.

Into thin air.

The key component in the era’s aircraft was the engine. It had to generate as much power as possible, operate reliably and be light, too. On top of this, there was the problem of a drop in air pressure. Normal combustion engines already experience a considerable loss of power at relatively low altitudes. In the case of cars on the ground, this only ever has an effect when driving over mountain passes. But for aeroplanes it is a critical factor.

The supply chain.

Rapp Motorenwerke GmbH in Munich built aero engines, but they were plagued by major technical defects. To remedy the problem, it was planned to manufacture under licence from Austro-Daimler, with Austrian officer Franz-Josef Popp overseeing production. However, Popp also advocated appointing Max Friz, an experienced design engineer who had just applied to join the company. When Friz took up his new position at the start of 1917, things were looking far from rosy. The factory was to be downgraded to a pure assembly plant for Benz and Daimler engines, and stop work altogether on its own designs.

The right man at the right time.

Max Friz had plenty of ideas of his own which he had not previously been allowed to implement – but which turned out to be pioneering. His design drawings alone were enough to set pulses racing among the military, who demanded the engine be put into production without delay. Partly in an attempt to consign the old image of failure to the past, in the summer of 1917 it was also decided to change the company’s name to Bayerische Motoren Werke GmbH. The new engine thus also received its definitive name: the BMW IIIa.

The straight-six unit with 19-litre displacement had an output of 226 hp. Friz configured the engine to be “oversized and over-compressed”. In other words, it was designed to work with the absolute oxygen content per cubic metre of air at an altitude of approx. 3,000 metres. That meant the engine had to be choked at ground level, as full throttle would have destroyed it. It was ingenious thinking.

Flawless in testing.

In December 1917, the first test flights got underway in a Rumpler plane and lived up to all expectations. By May 1918, the first production engines were already on their way – and went straight into active combat. Fitted in the Fokker D VII, one of the best fighter planes in existence at the time, the engine gave the military a degree of air supremacy over the Allies.

Pressure to succeed.

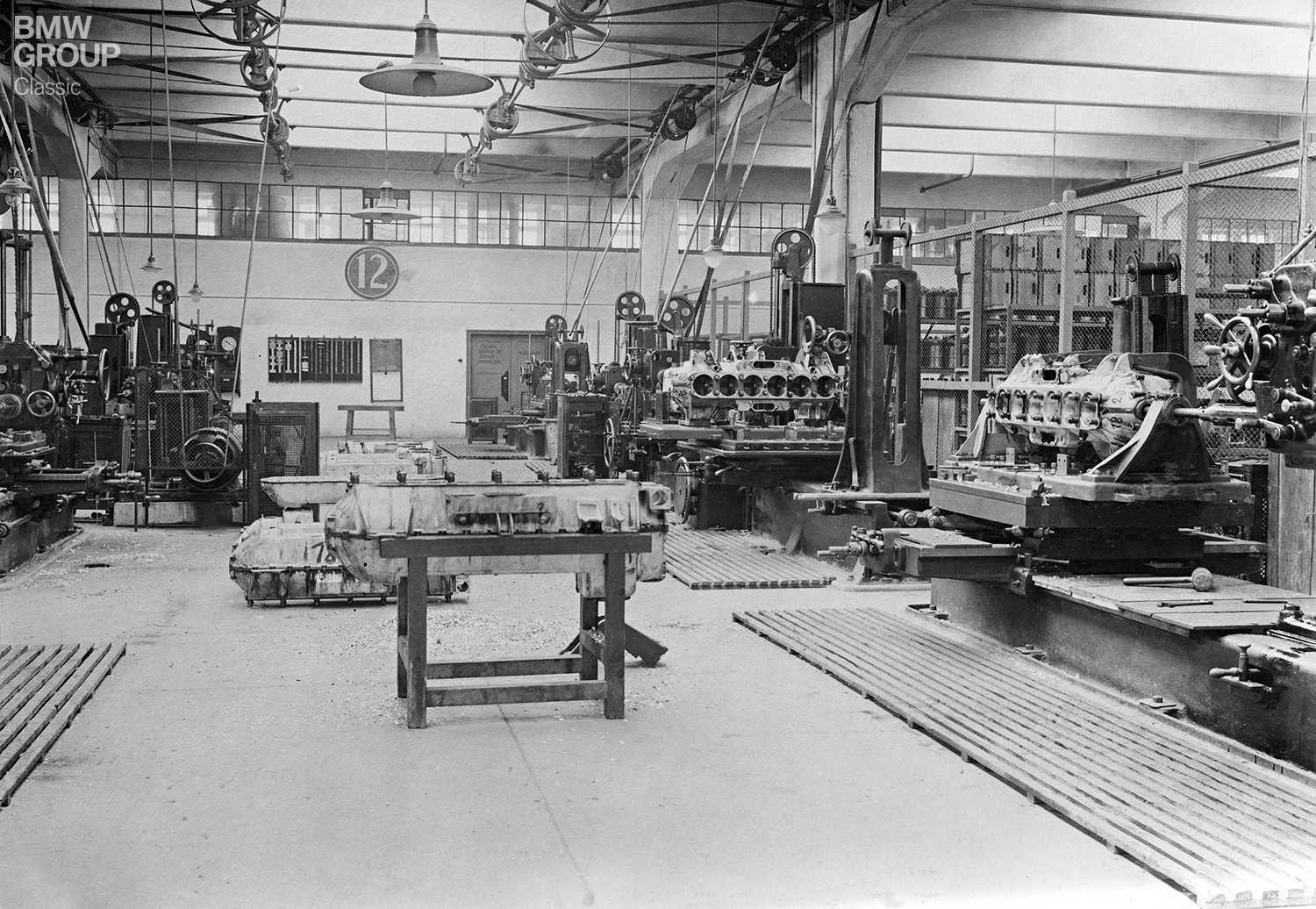

The military ordered 2,500 of these new engines. But the factory in Munich was not at all prepared for such a ramping up of production. A new plant was therefore built very close by, and the workforce swelled to nearly 3,000 employees. There had, however, long been a shortage of urgently required raw materials and there were even temporary power outages to contend with as the (mostly coal-powered) electricity plants had to economise. As the war entered its fourth year, the writing was on the wall for Germany. Ultimately, just 591 units of the BMW IIIa engine were built in Munich, and it failed to sway the outcome of the conflict.

It did, however, serve to establish the good reputation of a fledgling company that was to develop many more aero engines with great skill and expertise – one that, just a few years later, would also unveil a motorcycle of jaw-dropping excellence. Once again, necessity was the mother of invention, the provider of creative stimulus (isn’t that so often the case?). The R 32 was born. But that’s a story for another day.