The arrival of the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud in 1955 heralded the dawn of a new era. This was the first time the company had built a complete car – i.e. the chassis and the body were both in-house productions. But the classical coachbuilders were in no hurry to exit stage left in response. Instead, they came up with a delicious counterpunch to the appetite for undue haste: a two-door Drophead Coupé. Based on the Silver Cloud, it was born of dedication to tradition rather than slavery to fashion, a handcrafted one-off of the most exquisite quality.

The Silver Cloud ushered in a wave of change at Rolls-Royce. This was the model that kick-started production of complete cars at the factory in Crewe, England. No longer would the customer’s chassis be clothed by a renowned coachbuilder of their choice from outside the company. Yes, extremely robust, stainless steel underpinnings would still provide the foundations for the car. But the factory would now also shape the exterior design of its models. This was the moment when Rolls-Royce joined the series production ranks, at least as far as saloon cars were concerned.

In the 1950s, classical coachbuilders like H.J. Mulliner and James Young specialised in creating two-door “Drophead Coupé” convertibles. These open-top models cut a grand, imposing figure and confidently exposed their occupants to a vivid spotlight. They therefore laid on a very different on-board experience to that offered by a Rolls-Royce saloon. Where received wisdom had the Rolls owner hidden from sight behind curtains in the rear compartment, said proprietor could now be found behind the wheel, on first name terms with the sun and breeze.

“Adequate” performance.

When asked about the power produced by one of its engines, Rolls-Royce will traditionally reply with a genteel “adequate”. And there will be little in that description with which to quibble. The straight-six engine fitted in the Silver Cloud was tuned for smoothness and longevity, and – like a good butler – appeared content with an unobtrusive life in the background. It linked up with the silky-smooth Hydramatic transmission (fitted under licence from GM) to deliver the unhurried sense of opulence characteristic of every Rolls-Royce. A top speed of 165 km/h (103 mph) or thereabouts was perfectly respectable considering the car’s regal front end and around two tonnes of weight. Indeed, in the motoring landscape of the late 50s, there was little that could get near it. Servo-assisted brakes were a given, while power steering could be specified as an option. Not that most drivers would ever do anything as vulgar as push the car to its limit. As now, the magic-carpet comfort of a Rolls-Royce was beyond comparison and would instantly extract the tension from even the most highly-strung captain of industry. Plus, a convertible has a whole extra suit of calming attractions up its sleeve, not least closer contact with a charming landscape, should one be available.

Handmade by craftsmen.

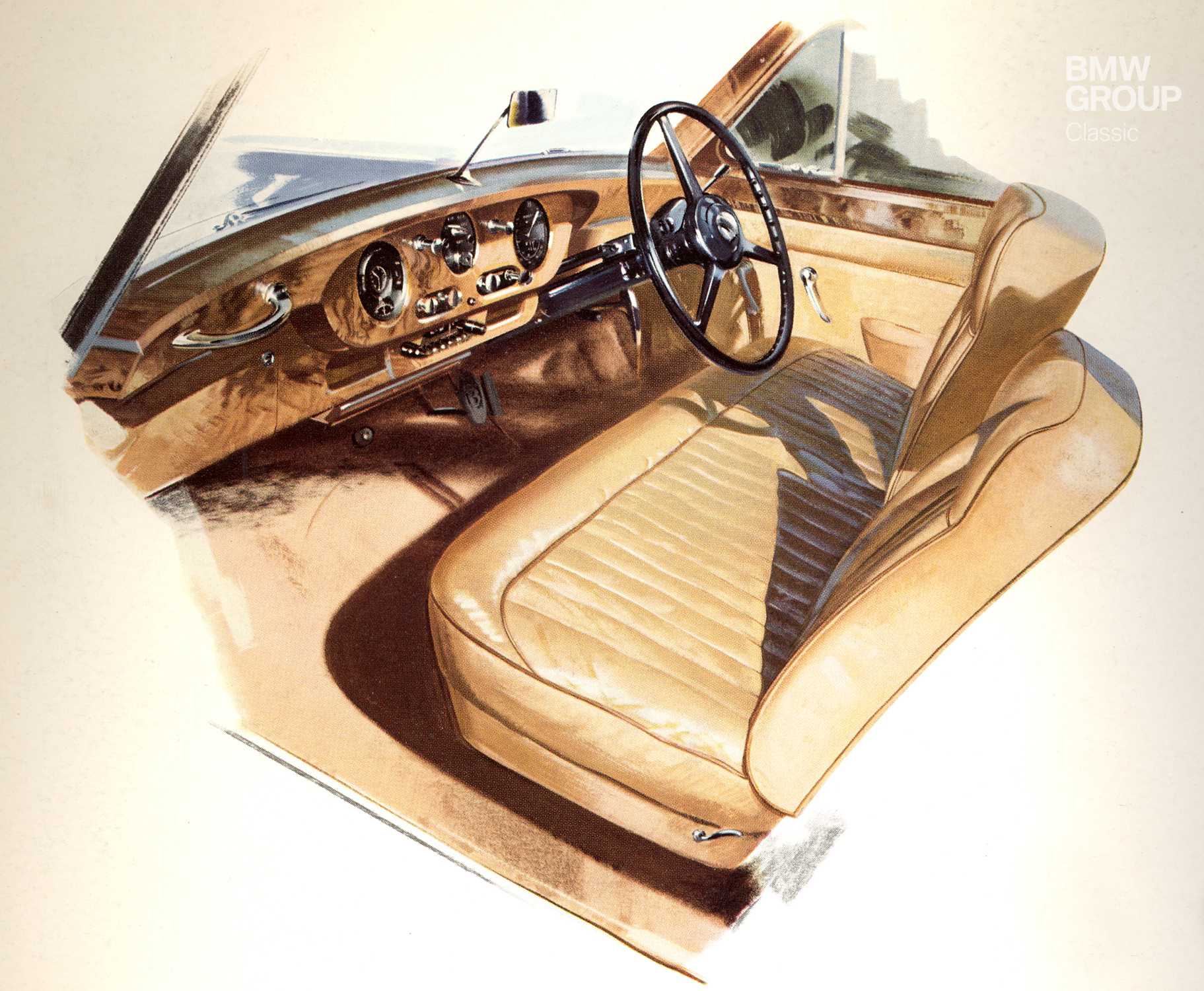

Wood and leather dominated the interior, as a Rolls-Royce customer would expect. The quality of workmanship was likewise reassuringly familiar and anyone perusing an example in the “original condition with some patina” increasingly beloved of classic car boffins will be able to see, feel and even smell the quality (a previous owner’s Churchillian penchant for cigars notwithstanding). All of this had its price, of course. But as the saying goes, if you have to ask how much a Rolls-Royce costs, you probably can’t afford it. An interesting point of note here is that, at the time, Rolls-Royce’s highly successful aero engine factory ran its car-building operation as something of a heritage-nurturing sideline and never turned it into a genuinely profit-making concern. The coachbuilders specialising in RR cars clearly saw things differently and made a very successful living from their trade. It’s nigh-on impossible nowadays to put a figure on how many Silver-Cloud-based Drophead Coupés were made, but sources suggest 22 were produced by H.J. Mulliner and three by James Young. Others refer merely to “a handful”.

Witnesses of days gone by.

A road tester at the time was fulsome in his praise of the Saloon in a 1957 issue of German car magazine “auto motor und sport”. He was particularly impressed by the overwhelming sense of comfort and the effortlessness of the driving experience. One somewhat prophetic sentence read: “We will have our work cut out to find a car that will rival the Rolls-Royce over its lifetime.”

A Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud Drophead Coupé was never simply “used”. Sometimes one would be sold on to a new owner, of course, but very often it would be handed down to the next generation. This was a car that embodied permanence, tradition and style like no other – and continues to do so today. Think country estate, but on wheels.