Small, practical and undeniably British, the estate version of the Mini bore its wooden veneer with a pride rooted in noble tradition. Not even the latest coachbuilding techniques of the day could compete. With their rustic charm reminiscent of a half-timbered house, it’s no wonder the Countryman and Traveller continue to delight owners up this day. Fans of the iconic Austin Seven Countryman and Morris Mini Traveller are certainly not a new phenomenon.

Vehicle body manufacturing was long the domain of the coachbuilder. Artistically crafted wooden frames formed the traditional skeleton of all vehicles. Metal panels and leather were attached to the frame with a multitude of small nails to form the bodywork. Extensive skill and knowledge were essential and the process could not be rushed. Change came in 1920s America, with the advent of sheet metal fabrication welding. This method was not only much more robust, but also considerably quicker: the all-steel body had arrived. Specialist and very large vehicles nonetheless continued to be built with wood and panels. Naturally, this included the first estate cars, which also had the benefit of looking great. An exposed wooden frame provided an attractive contrast to their painted metal panels and the technique soon became something that was not only a practical necessity, but also a luxury-led styling cue. The so-called “Woody” was born.

The revolutionary Mini.

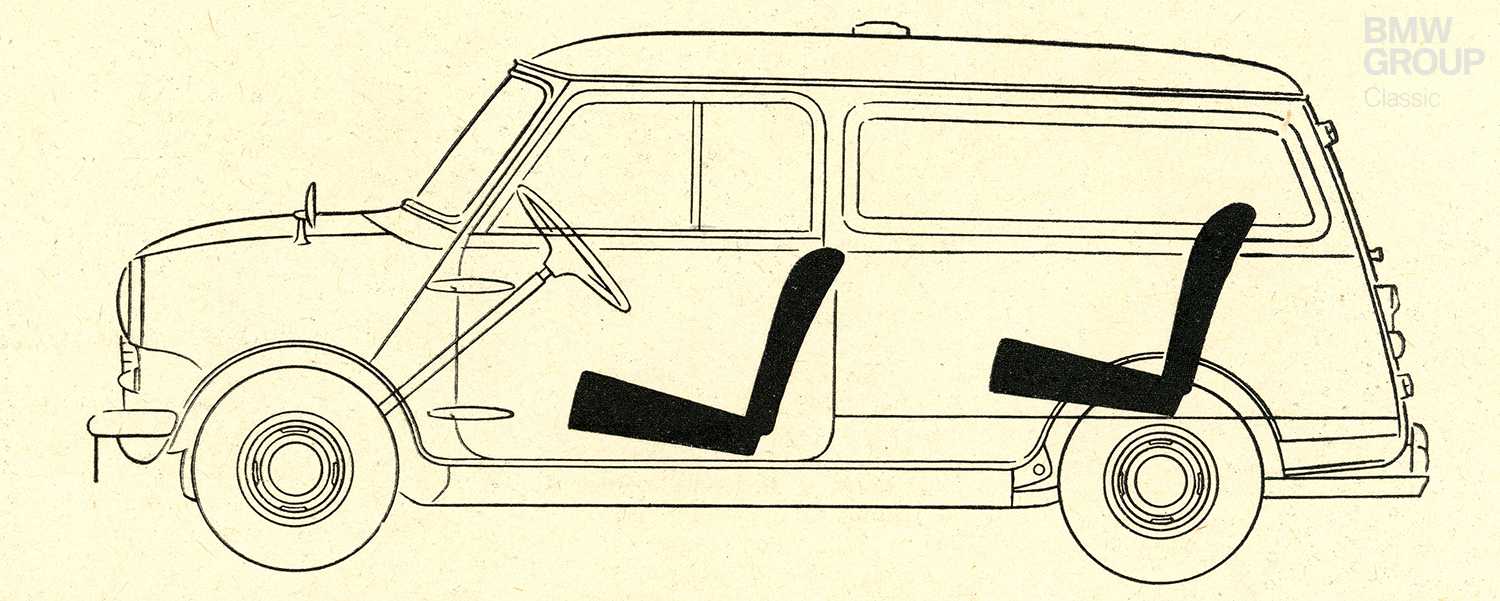

In 1959 Sir Alec Issigonis developed a small car that has since served as the template for a stream of modern successors. With its front-wheel drive and transversely mounted engine, the Mini was revolutionary. And, as with the enormously successful Morris Minor, it was natural that a practical estate version should follow. The Austin Seven Countryman and structurally identical Morris Mini Traveller hit the market in 1960.

The wooden struts of the B-pillar and rear frame are, of course, just for decoration (the modern, self-supporting sheet-steel bodywork of the Mini did not require additional stiffening). However, for conservatively minded buyers, particularly in tradition-loving Britain, the wood was evocative of the construction techniques they had always associated with practical estate cars. The two simply belonged together. And didn’t it still look fantastic – especially when set against the muted green or blue of the bodywork? The combination gave the thoroughly modern Mini a real sense of heritage. For export to other countries, the wood was soon abandoned and the more unadorned version was offered as an option in Britain, too. The context for the wood finish was not readily apparent beyond the shores of the British Isles and proved difficult to explain to buyers. After all, it had no function beyond capturing the hearts of those who saw it.

Technology from the original.

When they were launched, the Austin Seven Countryman and Morris Mini Traveller generated 34 hp from their 848cc engine. From 1967 onwards, these figures increased to 38 hp and 998cc, more than adequate for a car whose unladen weight was just 674 / 660 kg and which measured around 3.30 m in length. This more practically oriented Mini always came in the De Luxe trim level. From 1961, British buyers were offered the plainer version without wood trim, which cost 19 pounds less.

The “Woody” sixties.

Production of this attractive little estate car ended in 1969 with around 207,000 examples made. Its successor was the Mini Clubman Estate, which featured a brand new, slightly square-edged look. On this model, real wood was replaced by the wood-mimicking adhesive plastic film so beloved of Americans at the time. Gentlemen motorists held their tongues and sighed. Such are the perils for tradition over the passage of time.

This development also helps explain why the Mini estates with wood veneer still capture our hearts so readily today. But they come at a price, with their value heading in one direction only – upwards. If you want a left-hand-drive model, you’ll have to be especially patient; as we mentioned before, the half-timbered heritage never really hit home on the continent.