“Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” chimed enterprising US car dealers in the 1960s. Stock car races pulled in the crowds to oval tracks at the weekend – and grateful salesmen waved them into showrooms the day after.

Cola, beer and popcorn flowed as the average American family watched apparently standard family conveyances doing battle at break-neck speeds on the race track. The only standard – or “stock” – thing about these racing beasts was the shape of their metal; beneath the surface, high-performance engines pumped out extraordinary power and race tech pinned them to the asphalt. The show was the main attraction, but there was also something irresistibly refreshing about the cars’ humble origins. Winning races one moment, they could take your kids to school the next.

Old-world entertainment.

Europe was on a similar wavelength; here, too, down-to-earth sedans roaring to spectacular race wins held a certain everyman appeal. European customers, though, have traditionally taken a dim view of cars whose bite falls short of their bark. And there’s nothing like derestricted autobahns and twisty country roads to unmask any lurking charlatans. Drivers in Germany, in particular, are rather more eager at the wheel than their counterparts in the US, more likely to drive a sports car as nature intended. And Europeans show a far greater interest in the engineering and technology at their disposal than drivers across the pond.

M is for motor sport.

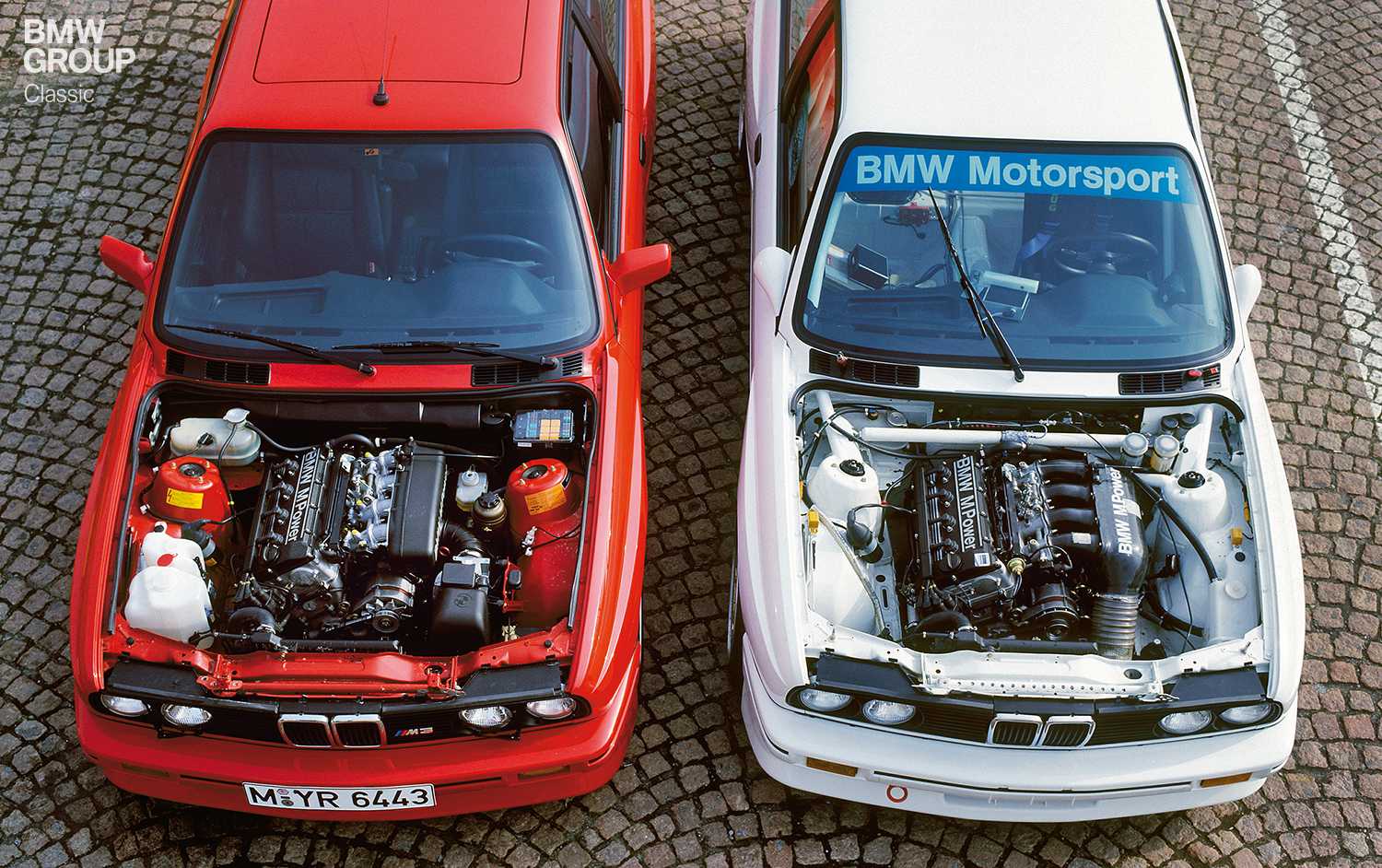

The appeal of the original BMW M3 was rooted – more so arguably than with any other car – in that most tantalising of prospects: the chance to have it all. Unveiled in 1985, here was a car that could handle itself on both the road and the race track. On initial inspection, it was just one of thousands of second-generation 3 Series Sedans pounding the roads. Yet at the same time it clearly had a few tricks up its sleeve. It caught your eye, then reeled you in. Flared wheel arches and an unmissable rear spoiler point to performance above and beyond what 3 Series-watchers had been used to (which, for the record, was already pretty impressive if you plumped for the 325i). Its flanks, too, were something of a departure from the “3er” norm, the rear window was more heavily raked and the boot lid a chunk shorter. Inside, there was the familiar, sporty tone to proceedings. But only when you opened the bonnet did the M3’s true secrets reveal themselves.

Where four hearts beat.

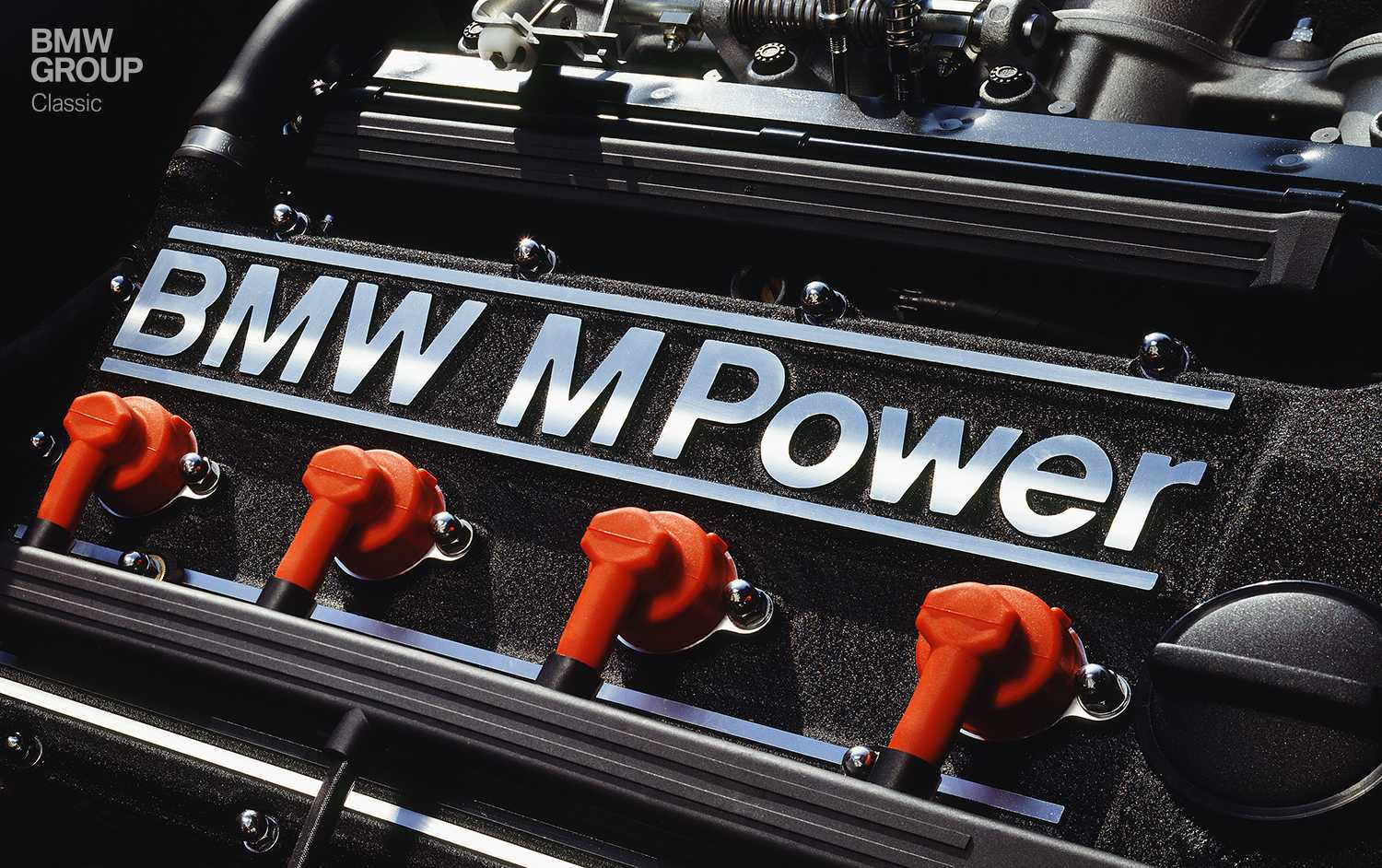

Taking its place ahead of the driver was a pure-bred, race-fettled engine with an unusually low cylinder count: just four. BMW and the 3 Series in particular are renowned for six-cylinder engines, of course. But the original M3 had no need or desire to “go large” for the sake of it. This was a genuine racing machine that competition regulations dictated had to be available in production-car numbers. An annual run of 5,000 units was required to gain eligibility for Group A events, and that meant striking a chord with sports car fans. The E30 M3’s four-valve, four-cylinder unit was a downsized version of the straight-six used to power the M1 and 635 CSi – both of which were enthusiastic ambassadors of high technology. Standard power was 200 hp from 2.3-litre displacement, and auto motor und sport’s stopwatch timed it at a brisk 7.8 seconds from 0 to 100 km/h [62 mph] in its first test in 1986 (the factory claimed 6.7 s). 0 to 180 km/h [112 mph], meanwhile, was dealt with in 25.8 seconds. The M3 could hit a top speed of 237 km/h [147 mph], which represented top-drawer performance back in the day – and that from a car dressed in a highly deceptive, highly practical compact sedan skin.

As road tester Götz Leyrer wrote in 1986: “The rev limiter is set at just under 7,000 rpm and, in low gears, the engine takes you there in an instant and without breaking sweat. Its linear power delivery is pleasure personified.”

The most successful touring car of all time.

The first-gen M3 could certainly cut it on the road, then. But it was born for the track, where it duly became the most successful touring car of all time. Barely a race weekend went by between 1987 and 1992 without an M3 in 300 hp race spec recording a win somewhere in the world. M3 drivers stormed to championship titles in Australia, Finland, France and Holland, and the car even tasted victory in the roughhouse arena of world-championship rallying. The victories and podium finishes racked up by the E30 M3 in the hotly contested DTM (German Touring Car Championship) alone soared from the many to the countless.

A love affair for the ages.

The “mk 1” M3 has long since entered the realms of the highly prized classic, with values only heading in one direction (through the roof). Properly looked after and sympathetically driven, these cars will notch up astonishing mileages. At the BMW Festival in summer 2016, proud owners were quoting figures in excess of 200,000 kilometres (124,000 miles) problem-free. Further proof, if proof were needed, that engineering designed to handle the rigours of racing will make light work of more prosaic everyday challenges. The E30 M3 combines a practical sedan with a race-honed sports car of impeccable history – to enthralling effect.

So it’s true. You really could win on Sunday and drive on Monday. To the office, on the school run, along your favourite back-road – and most likely grinning from ear to ear in the process.