The market for luxury cars has always been small (as well as perfectly formed, of course). But, as the 1930s got into their stride, the niche manufacturers in these rarefied climes were forced to engage with the same forces of progress as their larger industry-mates. Bespoke handcrafted models were being faced down by modern, volume-produced adversaries, and only by embracing change could they rise to the challenge. Cue the Rolls-Royce Wraith of 1938, which heralded a raft of striking new features designed to bring it into line with the zeitgeist. The Wraith celebrates its 80th birthday in 2018.

While it was boom time for Rolls-Royce aircraft engines in the late 1930s, the company’s car branch – small in size but exalted in terms of history – faced a fundamental threat. Increasingly sophisticated volume manufacturing techniques had thrown down the gauntlet to traditional craftsmanship, forcing the “old school” to explore new avenues to avoid being cast adrift. William Robotham, the chief engineer at Rolls-Royce’s chassis division during this period, travelled to the USA in 1934 to study new manufacturing techniques across the “pond”. Back then, nobody else on the planet could build cars as consummately and efficiently as the Americans.

Robotham returned to his native patch realising he didn’t need to make all the parts for Rolls-Royce cars himself when others could do so equally as well for less outlay. The engineer also wanted to modernise production and significantly increase output; he was convinced that car manufacturing at Rolls could only survive if the company upped its sales. This determined foray into the future was encapsulated by the Wraith – in this case, the most welcome of ghosts.

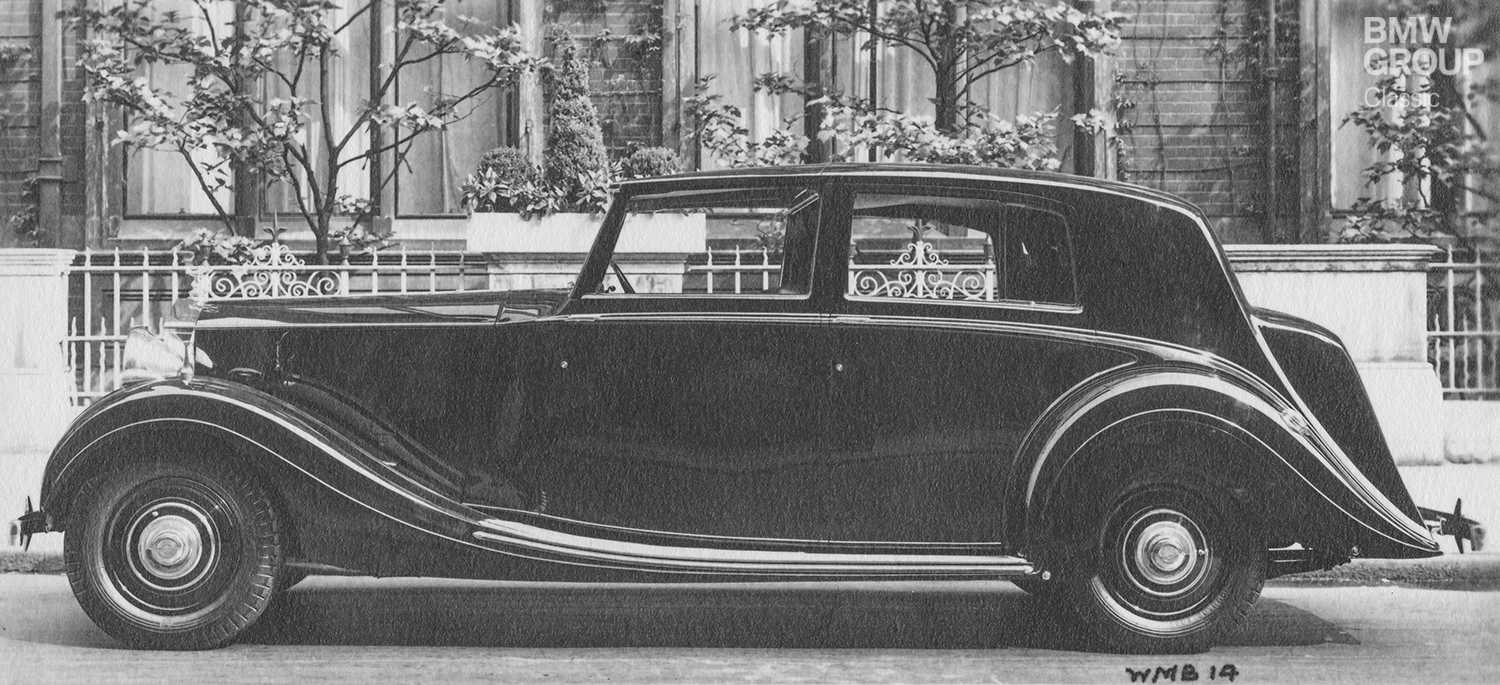

Looking ahead – the Rolls-Royce Wraith.

The chassis engineers for the new car took their cues largely from its sister model, the Phantom III complete with independent front suspension, adjustable shock absorbers and a hydraulic jack. The frame, including braces, featured numerous bored holes to reduce weight and, in contrast to the Phantom III, was partly riveted rather than welded. Power came from a six-cylinder engine with aluminium cylinder block and 4,257-litre displacement – a heavily revised and much lighter version of the unit employed in the car’s predecessor, the 25/30 H.P. Making its debut in a Rolls-Royce, the Wraith’s fully synchronised four-speed transmission was bolted directly to the engine. This was also the first Rolls-Royce without an ignition lever on the steering wheel, as firing up was now an automatic affair.

Bodies designed to individual specification.

As was traditional, the bodywork for theWraith was entrusted tospecialist firms such as James Young, Mulliner and Hooper (to name but a few) and designed to individual specification. When London-based Park Ward slipped into the financial mire during the economic slump of the 1930s, Rolls-Royce stepped in to first acquire a stake in the coachbuilder – before taking it over completely a few years later. This was certainly a neat way of expanding the company’s in-house capabilities.

The Wraith’s lifespan was cut short in 1939; only 491 examples had been built when war intervened. Fast-forward to 1946 and the Silver Wraith picked up the baton, the pre-war model rising from the ashes in further modernised form to play a major role in the company’s new wave of success. Today, the Wraith stands as a monument to progress and change.

YouTube video tips:

The Rolls-Royce Wraith at a concours d’elegance in Quebec, Canada:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2ncfmV1sf0

A proud owner shows off his Rolls-Royce Wraith:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LlHN3tqNkRk

A James Young-bodied Rolls-Royce Wraith from 1939 is presented here: